Recently I was asked how long I’d been working in the investment world. It’s a bit like being asked your age: when you are younger you want to be older but when you are older you’d quite like to turn back the clock. Similarly, when you have three years’ experience on your CV, you’d like to be able to say 10. But when it says 30 years, well, it would also be okay if it still said 10!

Anyway, my number is 30 years (just over in fact), and during that time I have helped clients invest through a variety of environments. For me, the excitement began with the collapse and bailout of Long Term Capital Management in 1998 and a US$3.65 billion bailout from a group of banks – a very big number back then – and the repercussions were felt globally. This was followed by the technology bubble that grew through the 1990s, only to burst in spectacular style in 2000/2001. After this came 9/11; the Enron accounting scandal; the 2008 subprime and subsequent global financial crisis; the European debt crisis in 2012; Brexit and then, of course, Covid.

Fast-forward and, even taking all of the above into account, it’s true to say that I’ve never encountered an investment environment as extreme as this one. On the one hand, the geopolitical backdrop is fraught with tension and anxiety: I’m sure that when we look back at this period in 10 years’ time it will be clear that we were going through a time of significant change. The same can be seen in equity markets where recent returns have been dominated by stocks that investors believe will be the drivers behind growth for decades to come – much of which will be AI-based.

This has been reinforced by what has arguably been the biggest influence on markets and investing over this century: the inexorable rise of passive investing via Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs). Today, about a third of all transactions in the US stock market are derived from passive flows (largely ETFs).

The result is a seriously elevated level of concentration risk (the percentage of total assets in certain stocks or sectors), which is at its highest level for about a century. The oft-highlighted Magnificent Seven now make up almost 20% of the MSCI World Index. Yep, if you’ve done the maths, that’s 20% of the market capitalisation of the global stock market!

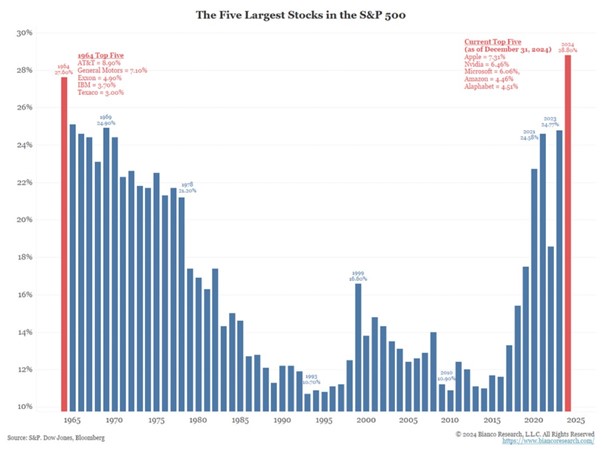

The following chart from Bianco Research puts some historic perspective to this type of concentration risk…what could possibly go wrong?

This is the S&P 500 (US Equity market as opposed to the World Index) and in a recent article in the Telegraph, Mark Hawtin, Head of Global Equities at Liontrust, highlighted that the last time we experienced such concentration was during the early disruptive phase of the Industrial Revolution. He goes on to say that: “in the late 1920s, US Steel dominated the market with a market capitalisation that accounted for 8pc of the country’s GDP at the time. Ultimately, however, it was not US Steel that yielded the best returns for investors as the Industrial Revolution unfolded. Instead, opportunities shifted from “enablers” to “businesses built on the existing infrastructure”.”

This was also true at the turn of the 21st century, when many companies we invested into were perceived as the drivers of the future but faded in importance from that point on. As ever, over the longer term there were winners and losers. Microsoft, for instance, was a big winner through the 90s, but if you bought Microsoft at its high in 1999 it would have taken you more than 15 years to make your money back. This is also true of other giants of the time, such as Cisco and Intel. Over the last decade, however, Microsoft has absolutely thrived and is, of course, one of the Magnificent Seven. Oh, and it currently makes up a measly 4.3% of the MSCI World index!

In simple terms, when we think about investing today it is really important to understand the environment. And it is, as I say, one of extremes: whether the geopolitical backdrop, the level of concentration of market returns coming from so few stocks or, on the flipside, the relative value of stocks from unloved sectors such as cyclicals. This clearly makes for an “interesting” challenge and it is clear to us that nothing is a given. Change, as sure as night follows day, will come.

Of course, we could have another year where returns are generated by a handful of stocks as investors continue to bet on those incumbents remaining dominant drivers of global growth. Equally, we might see investors broadening their horizons – recognising the risk associated with this over-concentration – and opting instead for the perceived value in out-of-fashion stocks (both growth and cyclical). As with US Steel and Microsoft in the past, we consider this conundrum to be the key: in short, AI could turbo-charge the future of all sorts of businesses rather than simply those of its creators.

Our objective never changes: we are committed to ensuring that these opportunities remain represented in clients’ portfolios – even as markets remain infatuated with their tech darlings. Nevertheless, and as we navigate inevitable change, it may very well become a stock-picker’s market. We are determined to be ready when it does!