Welcome to our 2024 fourth quarter Global Blue Chip Insights commentary.

In this update we will cover the following:

- Performance commentary for Q4

- Stock in focus – ASML

Global Blue Chip Q3 2024 performance commentary

Having covered, quite extensively, the year-to-date performance in our Q3 Insights, investors can read our usual performance report in the Q4 discretionary investment commentary, which can be found on our website. To round off 2024, which it’s fair to say 2024 was a gruelling year for the strategy, in this quarter’s performance review we will dissect what went right and wrong as well as identify what improvements can be made (as only hindsight allows us to do).

We faced a handful of major challenges in 2024:

- The dominance of the Magnificent Seven (‘Mag 7’), driven by a compelling AI narrative, investor flows, and leverage.

- Heightened volatility around information-sensitive periods such as earnings, as time preferences shrink dramatically.

- China’s economic woes, the inflationary pressures western consumers have been facing, and the impact on our consumer holdings.

These issues meant we held an unusually high number of ‘sea anchors’ in the portfolio, which compounded the impact of being underweight the primary drivers of the index’s return.

Mag 7 dominance, investor flows and leverage

The dominance of the Mag 7 as a weight within the market has been growing steadily since the end of the market’s sell-off in 2022. NVIDIA, for example, had a market valuation of ‘just’ $340bn in October 2022 and made up ‘only’ 0.69% of the MSCI World. At the end of December 2024, NVIDIA’s market cap had ballooned to $3.3 trillion and held an index weight of 4.7%. The Mag 7 collectively make-up 24% of the index, up from 19% at the end of 2023, and heir influence on returns has been spectacular, whether we like it or not.

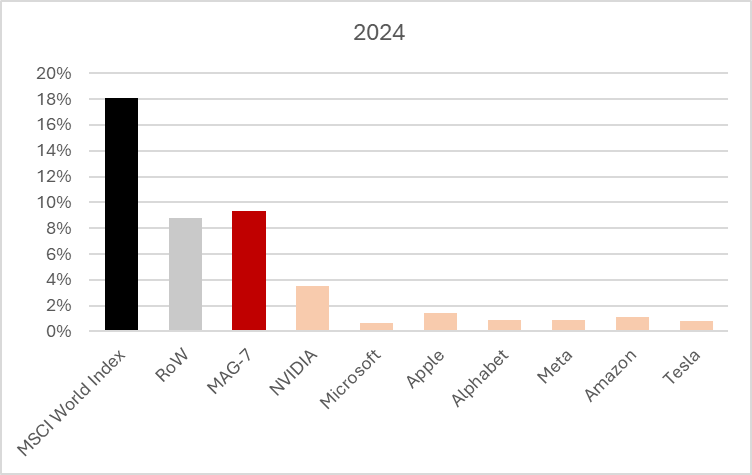

Chart 1. Mag 7 influence

The previous chart demonstrates their dominance, in USD terms, driving 55% of the overall market return throughout 2024.

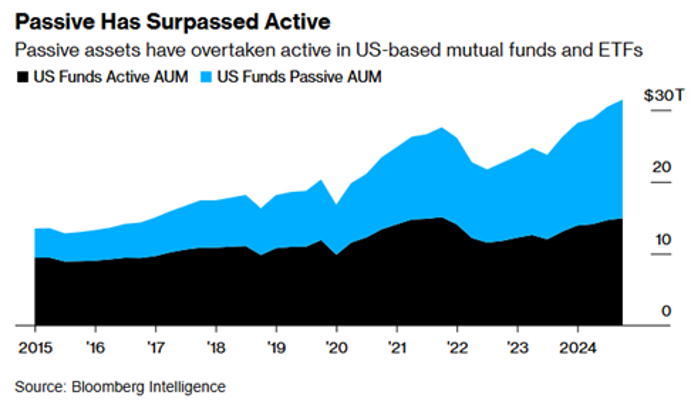

This collective has an even greater weight and influence in the S&P500 and NASDAQ indices at a time when passive investing has never been more dominant.

Chart 2. Passive has surpassed Active

In a study, Passive investing and the rise of mega firms, academics state that passive investing:

“…raise disproportionately the stock prices of the economy, and especially those large firms that the market overvalues. These effects are sufficiently strong to cause the aggregate market to rise even when flows are entirely due to investors switching from active to passive”.1

There is a constant stream of capital entering equity markets – especially in America, where investing in stocks is deeply ingrained within its culture. There are a number of incentives to support stock prices by the government and the central bank. High prices reflect well on the incumbent administration, they promote economic stability through the wealth effect and maintain financial stability. Moreover, there is a huge tax incentive to keep prices high as tax revenues are generated from dividend income and capital gains. US monetary policy is designed to maintain price stability and maximise employment, but the cocktail of low interest rates and quantitative easing (liquidity provision) has led to excesses working their way into financial assets, particularly equities. But, due to the way this excess capital works its way into equities - >50% through passive vehicles that replicate the overall market structure - it reinforces their distortive effects. The liquidity environment is becoming one of the most important macroeconomic factors to understand when allocating to equities.

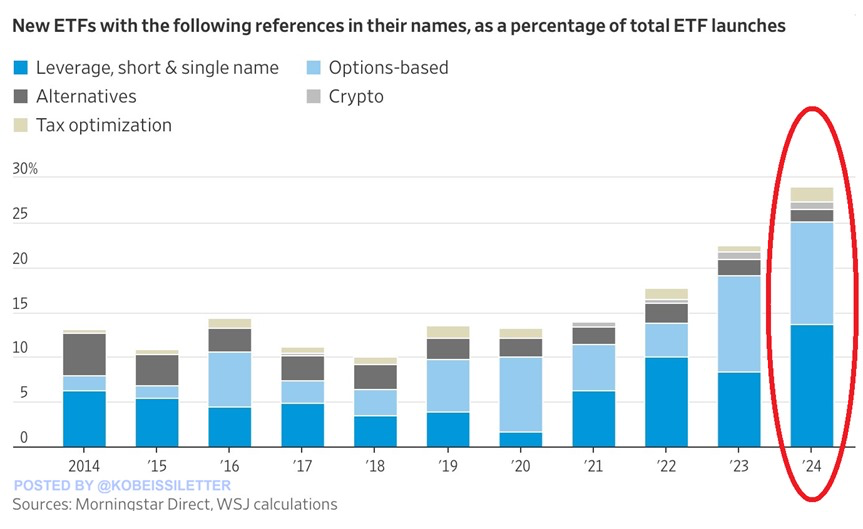

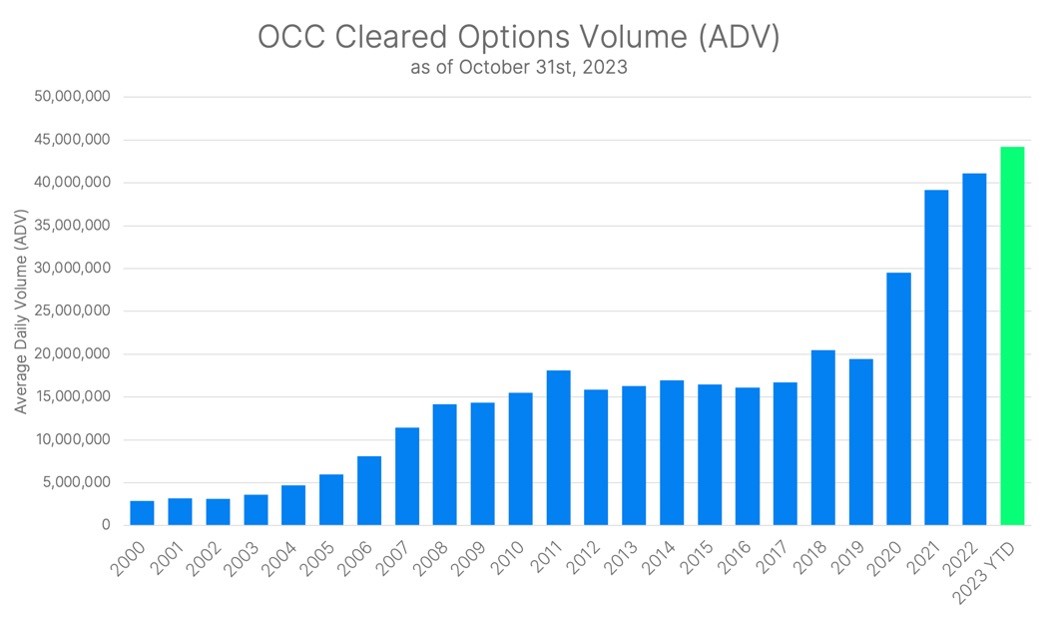

Another trend that we believe is exacerbating the distortion within markets and fuelling the outperformance of large companies is the growth in leverage, whether inherent through the use of derivatives such as options, or through the availability of direct credit lines (hedge funds and pod shops), or simple levered exposure through ETFs - an innovation made possible when the SEC relaxed rules on ETF derivative holdings. Today, investors can lever-up their exposure to a variety of assets, including single stocks, through these structures, and it doesn’t take much real money to move prices when its leveraged 2x, 3x, or even 5x. It is estimated that there is roughly $120 billion in leveraged ETFs and it was one of the fastest growing assets classes in 2024, at a time when option volumes have simply ballooned.

Chart 3. New EFTs with the following references in their names, as a percentage of total EFT launches

Chart 4. OCC Cleared Options Volume (ADV) as of 31 October 2023

However, leverage will eventually have to be paid back, adding to market volatility, as liquidity is withdrawn – we offer Q3 2024 as evidence of the impact a margin call on a grand scale can have. Many of the Mag 7 saw swift 20%-30% corrections in their share prices as leveraged Yen carry traders were caught offside by a surprise 10 basis point hike by the Bank of Japan! Liquidity has been called a coward because it’s never there when you need it and in a leveraged market, sharp downturns materialise as air pockets emerge and the natural ‘cash’ buyer can only be found at much lower prices.

So, what does the future hold? Without any regulatory intervention, passive investing trends will continue, promoting an ever increasingly expensive cohort of large firms that will further distort the return profile of the major indices. It will also leave indices increasingly vulnerable to exogenous shocks and idiosyncratic risks should these large stocks face significant operating headwinds. The reverse effect may also be a problem – will what gets inflated through continued flows also deflate if the trend in flows reverses as net savers head into retirement, turning into net sellers of stocks? That will most likely be an issue for another day. The popularity of passive investing is unlikely to reverse without some exogenous shock, policy or regulatory change, or for sufficient time to pass allowing the Baby Boom generation to mature into net sellers of equities. Therefore, the distortive impacts need to be better navigated.

Heightened volatility around information sensitive periods as time preferences shrink dramatically

We first witnessed this disturbing trend in October 2023 when Sanofi, a very big pharmaceutical company, revised down expectations for 2024. The reason wasn’t due to the trading environment but a decision by management to ramp-up R&D expenses to get assets within its pipeline approved, potentially securing growth for the remainder of the decade. For long-term stewards of capital this would be considered a sensible capital allocation decision. However, today’s market saw it very differently and the stock plunged 20%.

Chart 5. Sanofi stock downturn, October 2023

Although this was our first encounter with such volatility, it would not be our last. A number of consumer and life science holdings were subject to such volatility. This can be challenging for a focused strategy like the Global Blue Chip Fund. Navigating this type of volatility is a new challenge for us, one that we are quickly having to adapt to. After all, our edge is viewing opportunities over years, not quarters.

We monitor earnings to learn about developments and confirm management are still on track and in line with our expectations. If we learn of a change in strategy, we hear it first during these calls or investor days and we factor these changes into our original assessment and make informed decisions. What we have learnt in today’s market is that if a company announces an unexpected miss in expectations or revises down guidance, it is probably best to consider exiting the investment – even if the long-term strategy is intact. The selling in companies that have disappointed the market has been relentless and, whilst time arbitrage opportunities (we discuss the concept of time arbitrage in our Q4 2023 insights) may well materialise as a result, entering at an attractive valuation point no longer pays off as negative momentum has its own inertia in this market environment. Like many others, we have had instances where we’ve entered a stock too early, or held on too long. The positive to take from these experiences is that we have since adopted measures to help avoid making these mistakes again. The major change is identifying catalysts that could alter the narrative (stock or industry specific), and we invite you to read our catalyst section overleaf where we work through a handful of examples.

Consumer facing businesses grappled with a consumer that was slowing its rate of consumption. We are exposed to consumers globally, but our main exposure is principally to Chinese and American shoppers.

China’s economic woes stemming from a property crisis have been well documented of late. A deflationary bust is a real threat and it’s stalling the momentum behind China’s transition from an export-driven economy to one driven by domestic consumption. This took a while to play out as many company management teams in the consumer space were often keen to impress that they expected the Chinese consumer to return. They have yet to materialise, a crippling confluence of issues (over indebtedness, high youth unemployment, a decreasing wealth effect, a declining population, and an ageing demographic) is now too big to ignore and has evidently become too big for Xi to handle and the country teeters on a deflationary bust.

American (along with European) consumers faced a completely different challenge altogether; one of inflation and its corroding impact on purchasing power. Evidence of this comes in the form of discount brands doing rather well at the expense of premium brands. We know this from the reports of retailers who are noting a sizeable shift in ‘down trading’, and discount stores recognising an increase in shoppers whose income brackets far exceed their usual patrons.

The official data pointed to a strong consumer, but many ‘main street’ company reports pointed to volatile trading conditions that played havoc with inventory management and margins.

Jupiter’s Dynamic Bond team (the Jupiter fund being one held within the Ravenscroft Income and Balanced funds) summed up the complex nature of the data very well in a note to investors:

“We would argue that part of such inconsistency comes from the strong divergence that characterizes the US economy today. A small subset of very large corporations is seeing most of the growth in profits and a restricted cohort of very wealthy consumers is driving most of the spending. In the meantime, a large number of small and medium sized enterprises struggle to cope with an environment of high financing costs and less profitability, driven by resistance to bear further price increases from the large share of lower income households.”

The big question now is when will the macro picture improve for consumers? That is a question we don’t have the answer to, and it would appear management of a number of companies have also been caught off-guard. The Covid stimulus skewed demand for goods whilst supply chain disruption interrupted supply. Lockdowns saw a surge in online spending, further exacerbating the decline in physical stores. The result was higher prices, a very blurred picture of what future demand would look like, and what the preferred sales channel would be.

This noise has forced mistakes. For example, Diageo could not keep an account of wholesale inventories in Latin America resulting in a major write down and a significant headwind to sales growth in the region. Nike went all-in on its direct-to-consumer strategy under John Donahoe which worked exceptionally well during and just after lockdowns, but the neglect to wholesalers meant the shelves were filled by competitor’s shoes resulting in a loss of share in the physical market. These aren’t existential issues but, in an unforgiving environment, we have learned they have a toxic impact.

We’re not convinced being underweight the Mag 7 was the major issue. It would have helped, undoubtedly, but when we gross up our own technology picks to ‘market weight’ and compare the performance of our picks against the technology sector we get very similar outcomes.

From our perspective, the barbell approach of cyclical investments across consumer discretionary, technology, industrials and media, offset by defensive plays in consumer staples and healthcare, has served investors well in providing reasonable risk-adjusted returns up until this year.

The unusual number of ‘sea anchors’ and the actual underweight position to technology served to usurp our cherished record and we will endeavour to ensure this doesn’t happen again.

Catalysts

So what can we expect to come in 2025?

The portfolio is cheap, trading on a forward multiple of 19.5x which, for the quality, is exceptional value and we see a number of catalysts that could have a material impact on a number of holdings in the portfolio.

We offer three examples, one across each theme, of what we are seeing in terms of value and the catalysts that could change the narrative and the performance of their shares.

Oracle has been a beneficiary of the AI capex boom as Oracle Cloud Infrastructure offers cost effective solutions to customers looking to train and utilise their own AI models.

In September’s CloudWorld strategy day the company announced a number of targets:

- >$66bn in revenue by FY2026;

- >10% annual EPS growth;

- >$104bn in revenue for FY2029;

- and >20% annual EPS.

If management hit these numbers there is still value in the shares, despite the growth already experienced. We also believe there is additive growth outside of AI demand from the business’ healthcare strategy and continued transition of on-premise usage to cloud services – which may even accelerate in the age of AI.

Shares of Regeneron trade on 11x on fear that a biosimilar of Eylea will take market share. There’s no question that there are now significant competitive pressures to Eylea, but they’re overblown in our opinion. First of all, Regeneron already has a new and improved drug on the market (Eylea HD) and it’s significantly better than anything else available – management believe it’s going to be the new standard of care. The market is worried that Eylea HD is not ramping fast enough, but as management keep telling us, there will be an acceleration from roughly the half-year point when the pre-filled syringe version becomes available and when the range of indications and flexibility of use is expanded by the regulators.

It’s easy to lose sight of other 2025 growth drivers too – Dupixent is an inflammation-relieving drug that is simply gigantic, recording $3.82bn in Q3 2024 sales alone and continuing to grow at a good rate that doesn’t look like it will slow soon as it is approved for more indications. It is now the first ever biologic approved for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and we expect a nice contribution from this application this year.

Additionally, there is Libtayo - Regeneron’s newest blockbuster in cancer – which grew 36% in the nine-month to Q3 2024. And we expect it to keep growing.

We’re also due a pretty decent conveyor of pipeline readouts this year too – all with the potential to be additive to the “beyond Eylea” story. Perhaps, in particular, proof of concept for a new approach to obesity around the summer. As CEO Leonard Schleifer made clear at a recent JPM conference, the company has very big ambitions for the years ahead and it’s worth noting that the sell-side is always too pessimistic on Regeneron with a five-year view.

At 11.5x, Heineken Holding is at its cheapest since the last truly great opportunity for buying European stocks – the Eurozone Crisis. If you had bought Heineken Holding at that stage you would have seen the shares

more than double within four years, excluding dividends.

While we’re not suggesting the same thing will happen again, we do see the probability of making at least an 8% annual return from here , simply from dividends and earnings growth and, crucially, without any requirement for a normalisation in the P/E ratio. If the P/E normalises, shares will do even better.

If you follow the financial news, you’ll likely have seen persistent doom and gloom over the alcoholic drinks sector. It stems from two fears: 1) that new obesity therapies (Wegovy, Mounjaro etc.) will lead to reduced alcohol consumption, and 2) younger generations drink less than older generations. Both of these things are true, especially in the US – and for many, this apparently makes Heineken uninvestable. This, in our opinion, is a parochial US and Europe-centric view– not least because two-thirds of Heineken’s sales by volume are in developing economies, where trends look very different. Growth in the decades to come are expected to be from India and Africa in particular. But neither is Heineken standing still in the US or Europe, with long-term investment going into premiumisation, and low- and no-alcohol branded product development. As you would expect, we will continue to monitor this and update you with our view, but the strategy appears to be working.

At the last report in Q3, Heineken was still on track to grow its earnings quite nicely for 2024 (reporting an anticipated organic operating profit growth between 4%-8%) and we expect a positive development for 2025 too – is ‘the world not coming to an end’ enough of a catalyst to breathe some life into the shares this year? We hope so, and shares are certainly priced to benefit from any positive development in sentiment.

Stock in focus: ASML

ASML has been called “the world’s most important company you’ve never heard of”, and the epithet seems more than justified when you consider that it is the only company in the world capable of manufacturing the indispensable systems used to produce our most advanced semiconductors - extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines. Without these machines, there would be no AI or high-end smartphones.

ASML’s relative anonymity stems from it being a “pick-and-shovel” company buried deep within the semiconductor value chain, although at $200m to $350m per machine, these are expensive ‘shovels’. Being an understated Dutch company, rather than a brash Californian tech giant, probably doesn’t help either.

Given its inauspicious beginnings, few people would have bet on ASML’s current market dominance. The company was founded in 1984 as the discarded failed attempt by Dutch electronics giant Philips to break into the lithography market. However, within less than 20 years, through a combination of brilliant science, tenacity and its unique operating model, ASML went from rank outsider to market leader, overtaking the likes of Canon and Nikon along the way. Once it became market leader, ASML did not stop innovating, sealing its market dominance with the development of its EUV machines.

Moore’s Law, lithography and ultraviolet light

The extraordinary growth of the technology and electronics industries over the last 70 years has largely been down to the semiconductor industry and its pursuit of Moore’s Law. Moore’s Law is the observation that the number of transistors (tiny switches that control the flow of electrical signals, which enable devices to process information) on a microchip will roughly double every two years, a feat that has largely been made possible by advances in lithography. Leading-edge chips today contain in excess of 100 million transistors per square millimetre, with the design details measured in nanometres (nm).

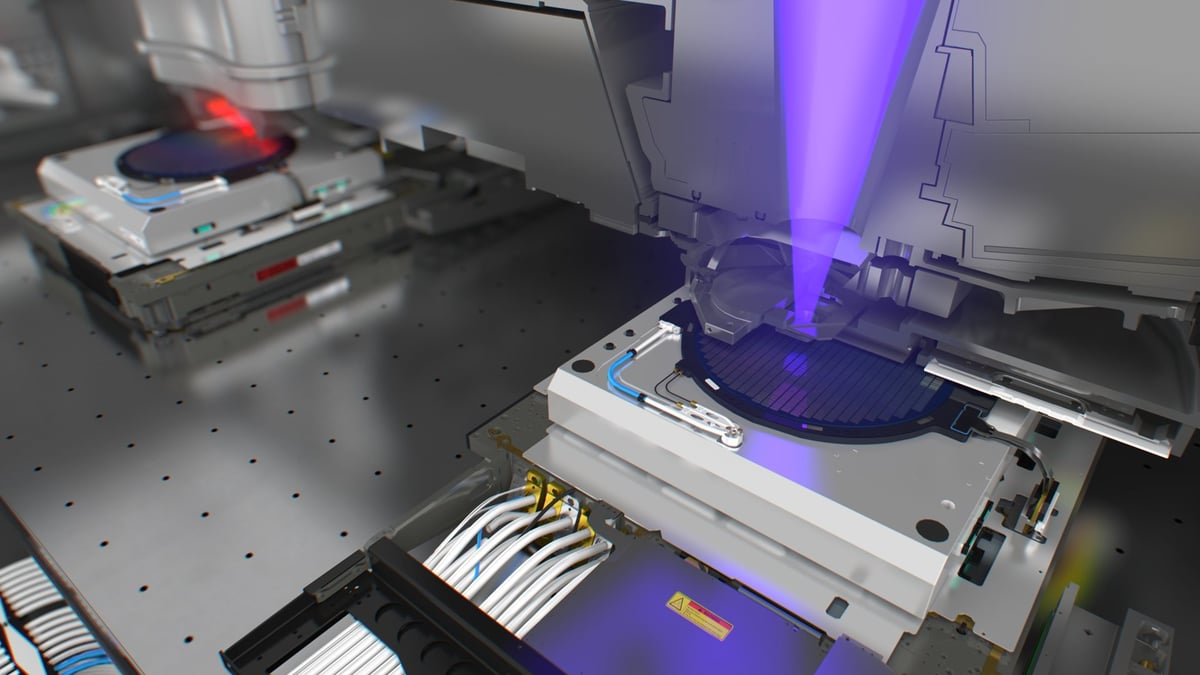

Lithography is the process used to create intricate patterns on silicon wafers, which are the foundation of computer chips. Early on, chipmakers used visible light to print these patterns, but as chip designs shrank to nanometer scales, visible light became too imprecise due to its relatively long wavelength. Imagine trying to write on a Post-it note with a large paintbrush—eventually, you need a finer tool. Today deep ultraviolet (DUV) light is used as the workhorse technology for mainstream semiconductor manufacturing, with ASML’s latest DUV machines using 193nm wavelength light to create features as small as 38nm.

However, making even smaller, more powerful chips required a completely new approach – an endeavour many deemed impossible. In fact, during the early 2000s Moore’s Law appeared to stall, as the industry grappled with this problem. Whilst EUV light occurs naturally in space, reproducing it on Earth is extremely challenging. Enter EUV lithography, which uses light with an incredibly short wavelength of just 13.5nm—small enough to print details at the atomic level. This breakthrough didn’t come easy. It took ASML nearly two decades and over $10 billion in research to perfect the technology.

These EUV machines are amongst the most complex machines humanity has ever built, each one the size of a double-decker bus. Transporting them requires three cargo planes, and installation takes over six months.

Despite the EUV breakthrough, the vast majority of semiconductor manufacturing still relies on DUV. Only the most advanced chips for AI, high-performance computing, autonomous driving and premium smartphones need EUV. That said, ASML also dominates the DUV market with a 90% share in the highest performing “immersion” DUV systems and a 65% share of the remaining “dry” DUV market.

Operating model, moat and growth drivers

ASML doesn’t just rely on its market-leading technology to drive growth and protect its business, it also has a flexible business model built on symbiotic relationships with both its suppliers and its customers. ASML often co-develops and co-invests with its suppliers in the technology it needs, thereby enabling it to operate as an asset-light system integrator with ~80% of its cost base made up of supplied components. This flexible approach also extends to the modular design of its products which allows for lower-risk product development, easier maintenance and simpler upgrades. The company also has a policy of not abusing its monopoly position, sharing the increased profitability of product enhancements with customers and suppliers.

This close-knit ecosystem, combined with decades and billions of dollars of R&D, creates a significant competitive moat. While competition is possible, the technical and financial barriers are extremely high and would likely require significant government support. Meanwhile, ASML is continuously moving the goalposts, as we can currently see with its investment in the next iteration of EUV.

Given its unique position at the heart of the semiconductor ecosystem, ASML is ideally placed to benefit from the relentless digitisation of the global economy. Whilst its ‘legacy’ DUV machines will be a key beneficiary of the rapidly growing semiconductor industry, the combination of AI and ever more powerful digital applications will also significantly increase the need for its EUV systems.

Although semiconductors remain a highly competitive and cyclical industry, ASML’s combination of mission critical technology and an almost unassailable market position make it an ideal play on the long-term prospects of the industry. Whether NVIDIA manages to keep its strangle hold on leading edge AI chips is anybody’s guess. However, regardless of who designs the next must-have chip, what is almost certain is that it will be built on an ASML machine.