The long-awaited announcement of President Trump’s country-specific reciprocal tariffs turned out to be bigger than expected, and not in a good way. If all the announced tariffs take effect on 9th April, the effective levy (tax) on US imports will jump to 25%, the highest since the early 1900s and an increase of nearly 20% from the current level. The big question now is how other countries will react with four potential options: countering with their own similar measures, accepting high US tariffs as the new norm and adjusting around them, negotiating for lower rates, or a combination of these.

Market reactions

US markets, predictably, reacted negatively, with equities falling hard, bonds rallying and the Dollar weakening. So far, the reaction in European and Asian markets has been more muted. Perhaps this is because, to some extent, we now know the worst-case scenario and markets had already significantly discounted the news. Or maybe markets are adjusting to the new world, which is not necessarily as negative for financial assets as first feared.

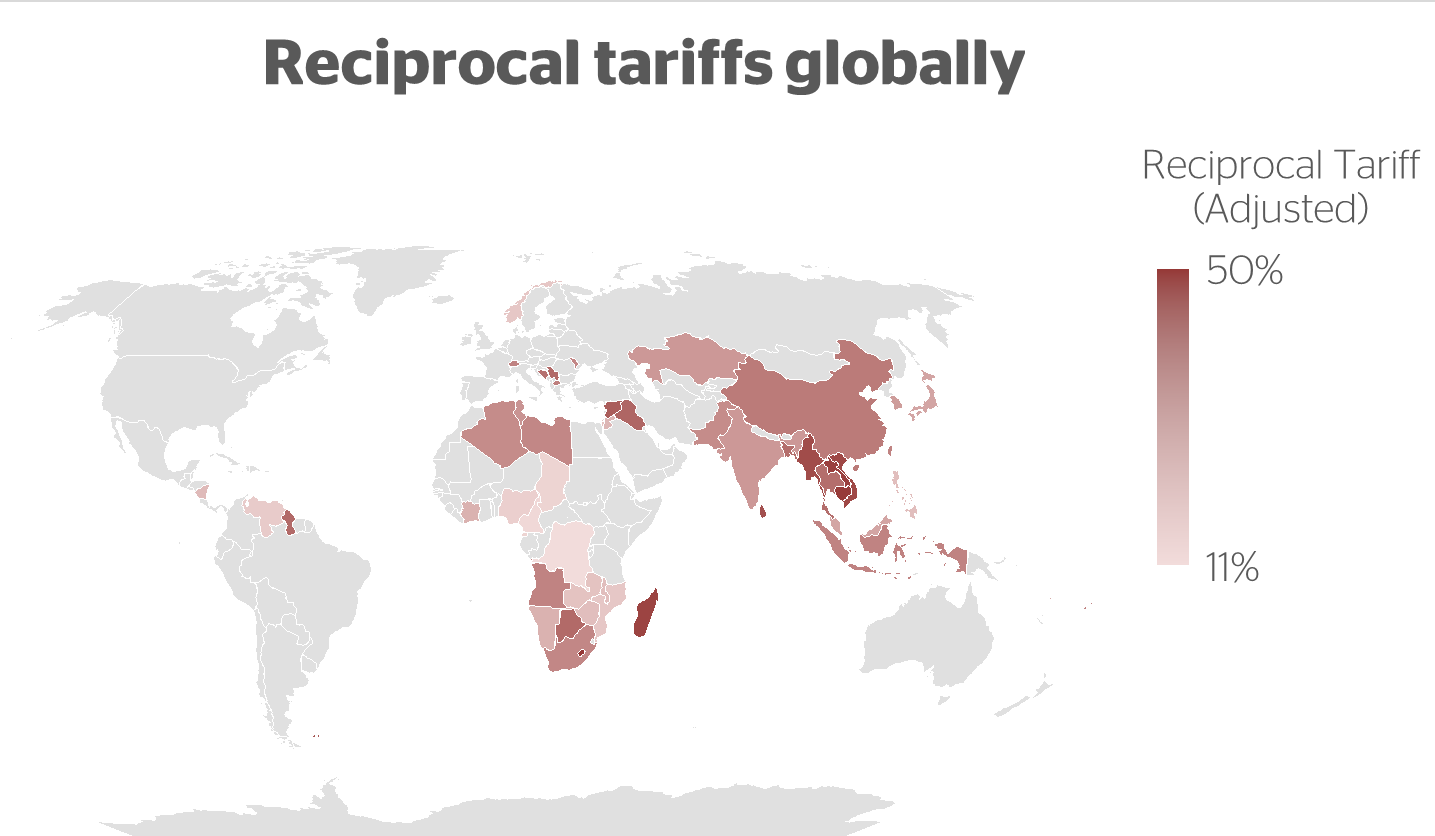

In general terms, Asia has been hit very hard, particularly in China and Vietnam. Canada and Mexico have got off lightly whilst Europe and Japan sit somewhere in the middle. If fully enacted, the tariffs will raise a maximum of c$770bn in additional customs duties, equivalent to 2.3% of US GDP. However, this will be reduced assuming that such high tariffs lead to a big decline in imports and a drop in demand.

The impact on the real economy depends crucially on what the US government does with the additional tax revenue. If it is given back to consumers via tax cuts, then growth may hold up well. If it is used to reduce the budget deficit, then this amounts to a significant fiscal tightening of more than 2%, which could well push the economy towards a recession. In terms of US inflation, since imports account for roughly 10% of consumption, the proposed increase in tariffs would add around 2.4% to the CPI price level, pushing inflation above 4% by the end of the year. Under these circumstances, the Federal Reserve would likely keep interest rates on hold, even if the economy weakens materially.

The effect on growth, inflation and interest rates in other countries will depend on three key things: the extent to which the country in question is affected, the subsequent response of each country and any consequential changes in monetary or fiscal policy. If the tariffs are kept in place, then they could reduce Chinese growth by around 0.5%, whereas the hit to the Eurozone, UK and Japan would be smaller at around 0.2% of GDP. The inflationary impact will largely be determined by how each affected country responds but is likely to be less of an issue than for the US.

Broadly speaking, the negative impact on growth and the limited effect on inflation is likely to persuade central banks to cut interest rates. It would also increase the likelihood of a more aggressive fiscal easing in countries such as China and Europe. Vietnam, as a relatively small and low-income country, has limited options other than a depreciation of its currency or a hit to growth. China and Europe, on the other hand, may well decide that they have little to gain by bargaining with Trump and can focus instead on improving domestic growth through boosting demand and improving its industrial competitiveness at the same time as the US suffers a major slowdown or even stagflation.

Short-term risks vs long-term opportunities

In the short term, markets are likely to stay volatile and difficult to predict, since it will be weeks or maybe months before we get much clarity on where the global trade war ends up, the impact of this on world growth and inflation and the subsequent policy response. Equities are clearly more at risk of further declines as growth slows and corporate profits take a hit. Bonds should hold up relatively well, especially sovereigns, whilst currency fluctuations could also be wild with the Dollar likely to continue its gradual decline versus the other major currencies.

It's not all negative though - at some point later this year, equities will be supported by a number of factors including an end to the tariff uncertainty, lower bond yields, fiscal easing in many economies, a weaker Dollar, lower energy prices and significantly cheaper valuations after recent market weakness. This will present an excellent opportunity to increase exposure to equities, although the recent shift in market leadership away from the US and growth stocks towards Europe, Asia, value and early cyclicals will likely continue for some time.

The long-term objective for the Trump government is to lower bond yields and interest rates, reduce the fiscal and trade deficits, bring down energy prices and strengthen US manufacturing and GDP growth. They may well succeed in their aims and it would be foolish to totally discount the possibility but there is a growing risk that the changing world order and fracturing global economy lead to the end of US exceptionalism and a rise in the fortunes of Europe and Asia.

Either way, a different and more flexible investment strategy will be required to that which delivered successful returns for the period post-global financial crisis to the past year or so.