Alex Rich, ESG equity analyst in the discretionary investment management team, looks back at COP28

For those of you not familiar with the image above, please allow me to enlighten you. It is entitled ‘This Is Fine’, and it depicts “an anthropomorphic dog trying to assure himself that everything is fine, despite sitting in a room that is engulfed in flames”… How could this possibly have anything to do with the recent COP?

Well, for those of you who took our advice in the first COP piece to grab a hot cocoa to watch the drama of COP28 unfold, you may be able to sympathise with this image. So much importance was placed upon the outcome of COP and, despite scepticism, some of the optimism was justified and progress here and there has been made – but the overarching narrative of opposed parties playing roulette with the Earth for their own personal agendas has shone as brightly as ever, resulting in a compromised agreement which is somehow simultaneously a step forward but also neither here nor there.

Keep a hold of that cup of cocoa as we explore below COP28’s outcomes.

What was the big picture?

Let’s take a moment to reiterate the stakes that were on the table heading into this COP – 2023 is set to be the hottest year on record, ice sheets are melting at a faster rate than expected, wildfires have ravaged the planet from Canada to Greece, and floods have devastated places from South Korea to Greece. Wait, did Greece have both floods and wildfires? Yes. Either Zeus is out smiting again, or climate change impacts are truly coming to the fore.

It is these impacts which are becoming increasingly more visible, and hence making the importance of positive progress that much more necessary. Which is why it’s increasingly sad that, as of the start of COP28, pledges to cut emissions from about 130 countries and 50 fossil fuel companies were still resulting in the world being well off its Paris Agreement targets per International Energy Agency research. Prominent figures such as The Pope and King Charles III have recognised these failings with the King going so far as to echo the point above that “we remain so dreadfully far off track”.

COP, in theory, has the power to turn this fledging situation around, given it is the world’s most prominent global forum concerning actions against climate change. But rather than the stake of the world being given the mature, thoughtful, and cohesive debate it deserves, instead we find ourselves playing politics and witnessing countries trying to “score points” as UN Climate Chief, Simon Stiell, puts it.

Alas, this is the position we find ourselves in in most COP iterations and it would appear that it has been a case of rinse and repeat with COP28 – where we all let our hopes enrapture us before being dealt a swift backhand of reality that humans love to fight with one another.

But not to lull all of you into a complete pit of despair, there have been good outcomes to arise from this COP, particularly concerning climate financing and nuclear power as we shall discuss below. It’s just that the overarching construction of the COP outcomes is admittedly wonky, and in order to understand why we must first look at the role played by this year’s architect – the UAE.

Was the UAE a good host?

Despite concern going into the COP, the UAE certainly came out swinging with placing the Loss and Damage Fund top of the agenda and launching that on the first day of COP28. We shall discuss this financing in more depth later but that certainly set the tone and hope for progression to be made throughout this conference.

That tone and pace was set by Sultan al-Jaber, the COP President / head of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) / chairman of renewable energy company, Masdar. He is certainly someone who wears many hats, and someone who we noted to be in a unique position that could both understand the gravity of the situation at hand whilst also being able to communicate effectively with some of the biggest contributors to said situation, the fossil fuel companies. We feel that we have to tip our hat to al-Jaber for being a pragmatist throughout the conference and for being able to get a deal that all parties compromised to agree on in relatively good time.

His presidency wasn’t without hiccups though, with controversies emerging that the UAE had planned to make energy deals at COP prior to the event starting, and that he had supposedly denied climate science at a separate event in November. The former has been caveated with the positive agreements entered into during the COP, like nuclear energy and climate financing which were led by the UAE. The latter has since been claimed by al-Jaber as a misrepresentation, which in turn was supported by Jim Skea, chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, who has since stated that “Dr Sultan has been attentive to the science”.

So, all in all, the COP28 President has been impressive in many contexts, with many pledges and agreements being passed this COP, as well as the strong diplomacy skills at getting opposingly strong-willed participants, such as the US and Saudi Arabia, to the table to sign the agreement (known as the UAE Consensus). What has been less convincing than the COP President, however, is the UAE itself.

A few eyebrow-raising concerns standout regarding the UAE, such as the warm reception to the arrival of Vladimir Putin, the number of greenwashing bots on social media hyperbolising a clean-environmental image of the UAE which, at the end of the day, is a top 10 oil producer, and the restrictions that have been placed upon activists and protestors at COP such as not being able to highlight human rights abuses in the UAE, having to censor detainee names and censoring comments about the ongoing Gaza war.

One of the largest controversies though, and this largely stems from al-Jaber’s position at ADNOC and the UAE’s prominent position within the oil world, is the number of fossil fuel and carbon capture lobbyists that descended on this year’s COP. It has been calculated that there were approximately 2,450 fossil fuel lobbyists at COP28, meaning that they were one of the best represented parties surpassing most nations. Naturally, this was concerning to many and suggested that a coup had taken place with fossil fuel companies pushing their agenda over and above the greater good.

However, one should recognise that this is indeed more nuanced. Ultimately, and this is the harsh reality, fossil fuel companies need to be included in the transition shift otherwise other’s hard work will be for little in the grand scheme of things, plus we need traditional power at least in the short-term to survive. So, whilst people such as Exxon CEO Darren Woods came out with controversial comments that renewables have been too great a focus for too long, at the very least it meant Exxon and many others were included in the conversation and brought their innovations such as carbon capture, efficiency techniques etc. to the floor.

Positives have emerged from this, such as 50 of the world's top fossil fuel companies having promised to improve voluntary deadlines for emissions reductions by the middle of the century. Negatives are still present though with warranted cynics analysing these big companies’ investments and noting that they talk about clean technologies a lot more than they actually place money into it.

All in all, the UAE has been a mixed bag. The UAE as mentioned has had lowlights, particularly regarding the activism piece and perceived hypocritical nature of their hosting. But, perhaps this is a contrarian stance, we think – in the context of the negatives surrounding him beforehand – Sultan al-Jaber has been an impressive figure and has actually been able to achieve a decent amount within these two weeks and, whilst the compromises reached do not go as far as we feel is needed – more on that later! – at least he was able to achieve said compromises in such a divisive topic.

What were the key commitments?

What were these compromises and agreements reached we hear you cry! Well, as expected, the main three mentioned in our first article had starring roles throughout the two weeks – being climate financing, nuclear power, and the phase out/down debate. We also saw food as an unexpected entrant to the discussion, so we shall touch on all these below.

Climate financing

As mentioned above, COP started off with fireworks! And not the illegal kind which begin forest fires, but rather something even more exciting – actual, tangible policy. Tangible policy is rarely a phrase I get to use when discussing COPs, discussions more often than not fall into the aspirations category. And as I’m sure we all know from making New Year’s Resolutions, aspirations and actions aren’t always intertwined. But this agreement felt different from right off the bat, with delegates agreeing to launch the Loss and Damage Fund and multiple parties already announcing sizeable contributions. This is a step in the right direction for sure, though the developed nations contributing were quick to point out that this was in effect charity, and not an omission of historical omission guilt.

Furthermore, the UAE president then announced a $30bn fund for global climate solutions, which namely focused on providing funding to the global south. Then several big banks backed the Energy Transition Accelerator, an American programme assisting in the funding of developing nations to move away from polluting energy sources. We really got a sense of positivity and drive from the sudden onslaught of meaningful financing being put in place to assist those worst affected, but simultaneously the most innocent, regarding causation.

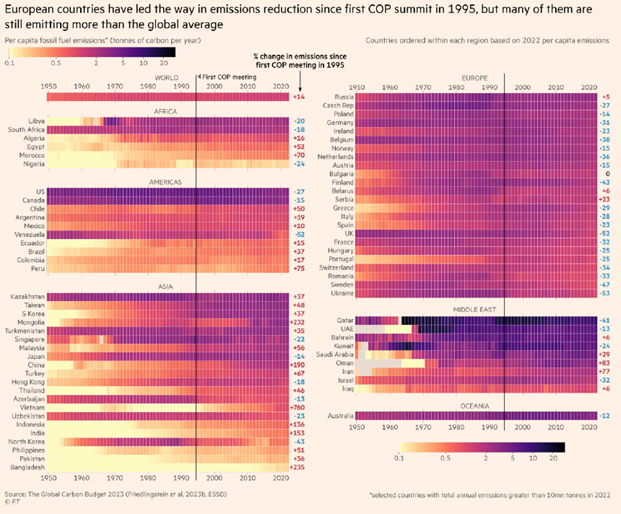

However, the party then got somewhat derailed as the two weeks progressed. It appeared that the teamwork and the smiles were all part of a collective façade as we then had to delve into the nitty gritty. One of the biggest hopes for this COP was the developed world being held to account for their historical contribution to the build-up of emissions – as demonstrated in this chart from the Financial Times below.

As we can see, richer and greater developed nations have played a significant role in emissions, and developing nations were pushing for proposed accountability, such that developed nations would commit to concrete future guarantees assisting with the transition, in addition to one-off commitments as noted earlier. However, the final text agreed at COP28 does not require developed countries to provide a greater volume of the support, and instead only “notes the need” for more finance to be directed to poorer populations. And, if the failure to mobilise $100 billion in climate finance by 2020 from a previous COP is anything to go by, we don’t hold our breath that these aspirations will be tangibly actioned soon. A lack of responsibility results in a lack of action.

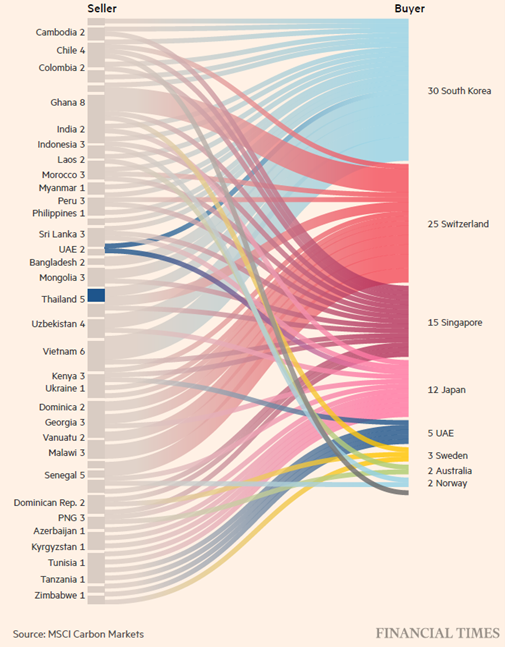

Stepping aside from direct climate financing (i.e., the provision of capital to allow nations to prepare for climate mitigation and adaption) for the moment, there has also been the big discussion concerning carbon credits (i.e., the use/gain of capital from the purchasing/selling of emission offsetting capabilities).

This too started with a positive bang in which the three largest carbon credit certification entities announced a collaboration to make their standards more consistent, hence providing more reputation to a sector shrouded in mystery and controversies – such as a study in 2022 which reported that of 40 Verra-approved carbon offset projects, most stopped none or only small amounts of deforestation.

It has been suggested by Morgan Stanley that the carbon credit market could expand from $2bn in 2022 to $100bn in 2030. So, it also came as welcoming news that the US’ Commodity Futures Trading Commission suggested standards that request exchanges to verify the quality of voluntary carbon credit derivatives, which base their prices on those of financial instruments bought by companies to offset emissions.

The ever-present cynic in us however remains concerned about carbon credits, not only for how to go about measuring the legitimacy of what one is buying, but also where future issued credits will arise from.

The chart above shows how land is being purchased by wealthier countries from relatively poorer nations in order to make business out of carbon credits. Whilst one could argue that developing nations are receiving an immediate payday in exchange for their land which could be put to good use, the other side of the argument is that this is a land grab with agreements weighed in favour of the wealthier nations taking advantage of the developing nations with worse legal infrastructure to prevent such eager-eyed inquisitors.

Nuclear power

Off the back of the carbon credit cynicism point, we can tone that down when it comes to nuclear power. We think the takeaways here from this COP can be considered a success. The most notable takeaway here is that 22 nations, including heavy hitters such as the USA, UAE, UK etc., came together to pledge to triple nuclear energy capacity by 2050. This is a step in the right direction in order to make meaningful progress to the transition away from fossil fuels, with what can be considered a relatively plentiful, renewable, and clean resource.

But… why is there always a caveat! The level of investment required for this is substantial and not explicitly discussed in the agreement. Furthermore, recent history is not on the side of the pledgers. 27 of the 31 reactors built since 2017 have been designed by Russia or China – not the US and its allies, this year Germany was in the process of shutting down its last nuclear plants, nuclear power plant construction is more than 40% cheaper in China and India than in the US due to factors such as smoother regulations etc. There are a number of hurdles which need to be overcome to make this pledge a reality, but we do hold sincere hope for this.

Something tangible (my new favourite word!), which builds upon our hope, is that it was announced at COP28 that a brand new nuclear energy summit would commence from next year. Scheduled for March 2024 in Brussels, we shall see global leaders gather to discuss how to put the aforementioned pledge into action – which is something we shall certainly be keeping an eye on.

Phase out / Phase down

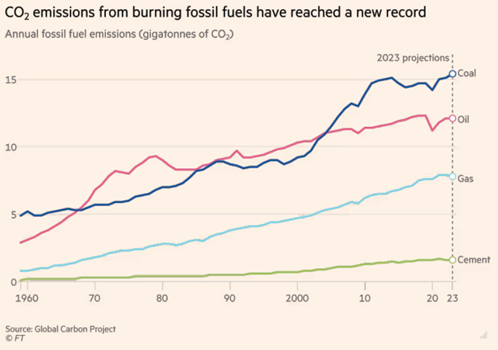

To phase out or to phase down, that is the question. Ok, admittedly that is not the direct quote from Shakespeare, but it certainly was the main question on everyone’s lips at COP28 and was the main reason we saw COP28 go into overtime beyond the last day due to strongly opposing viewpoints. First for context, please look at this this chart.

Carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels have reached a record this year and goes to demonstrate just how quickly the Paris Agreement targets are slipping from our grasp. And consequently, just how important this Shakespearean question is for the future of our planet.

Said question has certainly proven to be the most contentious of all the big points discussed at COP, and when the first draft COP agreement came out that was truly showcased through the presenting of three options:

- An orderly and just phase out of fossil fuels;

- Accelerating efforts towards phasing out unabated fossil fuels and to rapidly reducing their use so as to achieve net zero CO₂ in energy systems by or around mid-century;

- No text.

This shows just how mammoth a task al-Jaber was tasked with, with some nations wanting a complete phase-down of fossil fuels, and others not even pursuing the generally perceived bare minimum.

In the end, after a pulling an all-nighter (and not the fun kind), phrasing was agreed upon in that countries will “contribute... to transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems in a just, orderly and equitable manner". This is the first time there has been a clear reference to the future of all fossil fuels in a COP text – great! Plus, we’ll also be getting a tripling of renewable energy to boot! However, it doesn't include any explicit ‘phase out’ wording which is what many were seeking. So, we would argue it is safe to conclude that progress has been made, but on the basis that almost all countries stated afterwards that they had to compromise, then we can take it that the agreement does not have truly tangible strength.

One set of countries which was especially displeased was the collection of Small Island Nations who are particularly concerned about losing their livelihoods, and even their nations themselves, due to rising sea levels etc. caused by climate change. They have gone so far as to say they didn’t believe they were consulted upon the final vote, showcasing the power wielded by the larger more developed nations, and a potential imbalance in the decision-making process.

Ultimately, and similar to other key commitments, this is a step in the right direction and certainly a strong progression from the disappointment at last year’s COP. But once again, we’re faced with the uncertainty of how to tangibly transition away from fossil fuels – little detail is provided with this and, unfortunately, there’s enough flexibility in the wording that largely lets countries continue with their current practices to a certain degree, often with lip service and little incremental change being made. Carbon credits anyone?

Food

Finally with regards to key talking points arising from this COP, one which surprised us was the attention that food and agriculture received. Which, in hindsight, shouldn’t be too surprising given that the food supply chain accounts for approximately 20% of overall greenhouse gas emissions.

A pledge was made by more than 130 countries and recognises that what people grow and eat is a key factor in global warming. It is known as the Emirates Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems, and Climate Action. The parties are committed to integrating food into their climate plans by 2025, and it was signed by some of the countries with the highest food related emissions including China and Brazil. This is perhaps even in spite of approximately 120 meat and dairy lobbyists being present at COP28, triple that present at COP27, who most commonly had an agenda of convincing policymakers that meat was in fact good for the environment.

There are multiple ways in which this can be actioned, such as more carefully managing food waste, investment in more sustainable agriculture techniques etc. It is truly exciting that COP has finally recognised the significance of this sector and the necessity in which it needs actioning for future emission reductions.

It is admittedly a nuanced issue though, with the UN equally saying that ‘the world must ramp up the production of meat to address widespread hunger and nutrient deficiencies faced by people in developing countries’. There is certainly a balance to be struck.

Who were the key players?

Earlier this week we saw some equally big news in addition to COP28 – the largest sports contract ever has been signed with Shohei Ohtani agreeing to play baseball with the Los Angeles Dodgers for the next 10 years. In a similar way to Shohei, there are some countries that truly swung their weight around in the COP agreement process to get their way, and here’s what they came away with when they stepped up to the plate:

USA, UK & EU

- The US’ Financial Conduct Authority has announced a series of new measures intended to tackle greenwashing issues, including both investment labels (with criterion) as well as marketing guidance.

- Whilst there was no explicit mention of reducing methane emissions within the COP28 agreement, the US has recently approved new rules to crack down on methane leaks.

- The 10 largest concrete/cement companies in the world, many based in the UK, EU and US, have announced a new formal strategy to shift the industry to net zero by 2050.

- The UK has faced several criticisms during this conference, but the most prominent in the media have been concerning travel arrangements. Rishi Sunak, Dave Cameron, and the King all took separate private jets, and Graham Stuart, the UK climate minister (and UK’s COP28 top negotiator), did a ~7,000 mile round trip to and from Dubai the eve before the final agreement in order to participate in a House of Commons vote. Hardly projecting the image of climate concern.

China

- Over the past 10 years, China has added 37 nuclear reactors, for a total of 55, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency. By comparison, over the same period, the USA added two for a total of 93. And as per the progress made at COP28, China shall look to continue this trajectory.

- Whilst COP28 has alluded to expanding nuclear energy, China has been making an aggressive push to tie up global uranium supply, as per the boss of Yellow Cake.

- China has been critical of the vagueness surrounding climate financing, with the Chinese representative stating that "it is regrettable that the many important concerns of developing countries have not been taken into account".

Saudi Arabia

- Saudi Arabia had some pendulum movements throughout the COP process. They were arguably the most adamant demanders of phase down/out not being included, with their energy minister stating, resolutely, “Absolutely not” when asked. This position is sadly understandable from their perspective given that they are the leading figure within OPEC, though their argument that COP28 is placing “undue and disproportionate pressure against fossil fuels” is perhaps more dubious. In the end, they downplayed their stance and agreed to the pledge. Perhaps because “transitioning away” is softer wording than “phase down”, and also perhaps because they didn’t want to be seen as the main party opposing the agreement given the huge push they have done recently to clean up their image.

Russia

- Russia could play a significant role in the increasing of global nuclear power, which certainly throws a geopolitical spanner in the works to keep tabs on.

India

- India has tried to position itself as a pragmatist. Despite continued push back against its net zero 2070 targets for being too far into the future, which may very well be a fair point, India have responded stating that they are actually achievable and not solely aspirational – unlike many other nations.

- Despite the encouragement of transitioning away from fossil fuels, India’s reliance on coal has been growing, and it currently makes up nearly 50% of its energy sources. And the Indian government has said that coal will continue to be important for the country's growth.

- Modi has also launched a ‘Green Credits Initiative’. It has been described as a “mass campaign that goes beyond the commercial mindset of carbon credits”, apparently a new voluntary carbon offset programme to encourage tree planting. • India has proposed that it be the hosts for COP33 in 2028.

Brazil

- Brazil's national development bank (BNDES) launched the Arc of Restoration programme to restore ruined Amazonian woodland an area the size of Latvia, by 2030. With funding of up to $205 million through 2024, the programme would seek to capture 1.65 billion tons of carbon from the atmosphere by 2030.

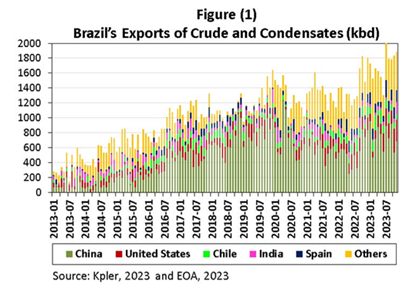

- Controversially, whilst Brazil has been leading the charge and was predicted by many, prior to the commencement of COP28, to be the star of the show – they have also recently made the announcement that they shall be joining OPEC+ at the beginning of next year. And their exports have steadily been increasing as we can see above. Is this the pot calling the kettle black?

The final SCOPe

COP28 this year felt a bit like a romcom. It was set in a slightly absurd location given the UAE’s presence in the fossil fuel realm, but the conference itself started off hot and passionate with a lot of good agreements and pledges being announced early on. We then hit a slight lull where we perhaps lured ourselves into a false sense of security that this COP would defy all the odds and really result in positive change. And then we hit the point in the movie where the tables turn and it suddenly goes wrong, which in our case was the first draft of the COP Agreement being hated by most for varying reasons. And then, through a process of Hugh Grant-esque muddling and compromising, we get the happily ever after – a signed COP Agreement.

Except was it a happily ever after? We got an agreement which is a positive, and of course it has taken us slightly further than last year – I mean at least for the first time ever we got mention that fossil fuels need to be transitioned away from! But one also can’t help but feel slightly deflated that the level of compromise most likely means that action will not be swift and resolute, and that the Paris Agreement targets are slowly but surely drifting away from us.

This ultimately harks back to what we have said throughout this piece, whilst it has been great seeing progress being made concerning nuclear power, climate financing etc., too often COP errs more towards aspirations rather than a tangible plan. However, unlike COP, tangibility is one thing we pride ourselves on here at Ravenscroft, and we analyse our investments on fundamentals and in the context of the changing world to make the best decisions for our clients.

Now, we can put our COP cocoa down till COP29 in Azerbaijan (another big oil exporter?!) and pick up our Christmas cocoa!